The Fable of the Bees by Jan Peter Hammer is an exhibition based on the 1705 poem by Bernard Mandeville “The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits.” In his poem and ancillary prose Mandeville brings into being the counter-intuitive argument that better people make the world a worse place, since so-called vices such as egoism or greed stimulate social prosperity, whilst altruism or honesty result in collective atavism and disinvestment. In spite of the harsh reception of Mandeville’s work, which gave great offense to contemporary readers, his core idea that private vices lead to an increase in public benefits was later recovered and popularized by the British Utilitarian School. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” parable is an off-shoot of Mandeville’s fable minus the cynical crudeness, with an added veneer of scientific respectability that makes the argument much more palatable and less contentious. Fables and parables are moral tales whose aim is to instruct, each of which contains a lesson to be learnt by its readers. Though 18th century’s classical political economy embraced a moralizing function, economics has since gone to great lengths to hide its ethical foundations. Claims of neutrality notwithstanding, choices of economic policy remain largely political.

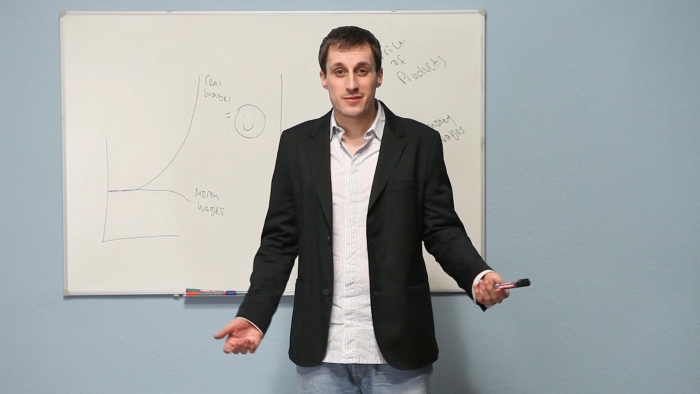

In Jan Peter Hammer’s eponymous video “The Fable of the Bees” – shot in the guise of a You Tube home-made production – an eager young professional unwittingly channels Mandeville’s reasoning, providing a good illustration of the adage that “practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”(J.M. Keynes)

The other work in the exhibition, “That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Unseen”, is a performance in which a hired security guard sits idly by a lump of cash, during the gallery’s opening hours for the whole length of the show. The guard’s task is to survey the money, yet the sum he is guarding is his own wage, which he will collect at the end of the assignment. That is, whereas the guard’s function is to watch over the money, the money’s function is to pay the guard for watching it. Reminiscent of Beckett’s literary compactness, guard and money are locked together in an absurd play, whilst in a Dadaist abstraction of the business cycle capital and labour cancel each other out. “That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Unseen” is a title borrowed from Frédéric Bastiat’s 1850 text “Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas”, in which Bastiat lays out yet another parable, the “parable of the broken window”. Positioning himself against Mandeville’s notion that destruction brings net-benefits, Bastiat states that, “In the economic sphere an act, a habit, an institution, a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently; they are not seen; we are fortunate if we foresee them.”

In our times of debt deflation and economic uncertainty what remains largely unseen is that though money has no price, securing its value comes with a high social cost.

Press release: Ana Teixeira Pinto