In 1965, a group of artists and theater-makers, collectively known as The Living Theater, headed by the Gesamtkünstler Julian Beck and his wife, Judith Malina, arrived in Berlin as a start to their self-imposed exile, after a series of futile court cases with the United States Internal Revenue Services (I.R.S.). Berlin, through the figure of actress Helene Weigel, opened its arms wide to embrace these great and radical artists. This year, 2014, Berlin, through the figure of the Berlin-based gallery Supportico Lopez in collaboration with the Fondazione Morra, will open its arms a second time for the homecoming of Beck’s art, with an exhibition of his paintings and drawings created between 1944 and 1958.

Julian Beck, born 1925 in New York City, is mostly recognized for his foundational role in The Living Theater—which name itself begins to approach the depth, versatility, and sense of human engagement that makes their work enduring still. It is a theater that lives, that allows all aspects of the human experience—political, religious, sexual, etc.—to form and to inform the work; it is a theater of change, in constant flux, a mode of theater that attempts to understand, and en route to understanding, a theater that comments on our world. However, Julian Beck began as a painter, and as a painter, he became a theater-maker. Beck’s oeuvre allows us to look at the living artist: for that which must be said is given the freedom to find its unique form, and in such an overflow of media, even a painter who no longer paints still inhabits and senses the world as a painter.

In 1943, Beck met his future wife and collaborator, Judith Malina. Together, they attended Erwin Piscator’s theater workshops, performing their earliest experiments in their New York City living room. By 1947, they began to envision a new kind of theater, which would soon be inaugurated “The Living Theater.” It would take however, nearly another ten years before they would receive recognition for their work, and which would be, concomitantly, around the moment when Beck would stop to make paintings. Whether Beck ever stopped to see the world around him through a painter’s sense of movement and color, is not our question. Beck perhaps stopped to make paintings in the conventional sense, because the Theater, in its fluidity and multiplicity of formal possibility, began to take precedence.

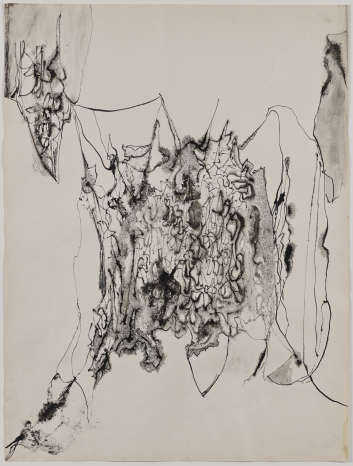

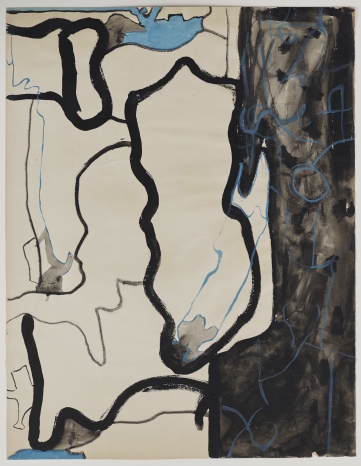

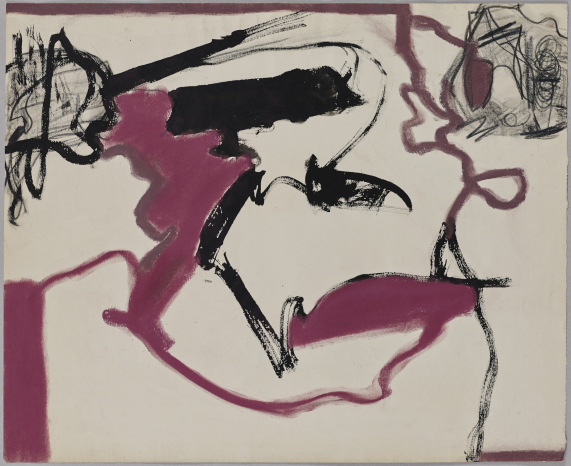

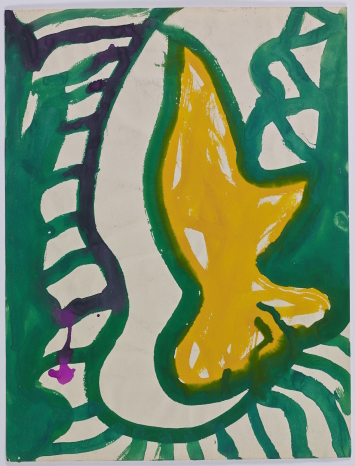

Surrounded by such landmark figures as John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jonas and Adolfas Mekas, Allen Ginsberg, as well as the artists around Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery, including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, as well as the older generation of European Surrealists, it could be said that Beck and Malina were deep in the nucleus of some of the most exciting and radical departures in the history of American art. Upon looking at Beck’s fecund body of paintings, drawings, as well as his set and costume designs, one cannot help but note the influence that this creative hive exerted on his work. But Beck is, first and foremost, an autodidact, and so is able to bring together such diverse influences into a vigorously idiosyncratic Weltanschauung—or perhaps his work arrives more closely to the word syncretic. It is as if the spirits of Mondrian, Kandinsky, Picasso, Cocteau, the Surrealists, as well as mystics, Norse Gods, and the bodies of Blake’s visions passed through his body to make an impression or, perhaps, with more urgency, an expression in charcoal, ink, pastel, oil, and collage onto the living surface of his support—his cave wall.

Beck’s earliest works were created roughly between 1941 and 1943, during his brief time at Yale University. Unfortunately, most of these works have been either lost, destroyed, or remain obscure. But, from what information we have about these works, we can confidently assume they were mostly ink drawings and other experiments produced by “an artist as a young man” still hacking his way through the thicket of external influence and self-discovery. His major influences seem to have been the Surrealists as well as Jean Cocteau.

Upon his withdrawal from Yale in May 1943, Beck returned to New York City, where he became acquainted with Peggy Guggenheim. And it is precisely at this moment that Beck self-consciously dedicated himself to making art. Around this time, all of the most important components of Beck’s later career began to roll into action—his friendship with Jackson Pollock and the other New York School artists, as well his introduction to Judith Malina. Works of this period were exhibited at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery; and seemingly in dialogue with the contemporaneous Abstract Expressionists, the paintings are “non-figurative” explorations of the tactility of his materials. And yet they go beyond craft: they grope toward an expression of reality in its fullness, toward the reality of the unconscious, as well as the pulse and experience of the world as it happens around a human being and his or her art.

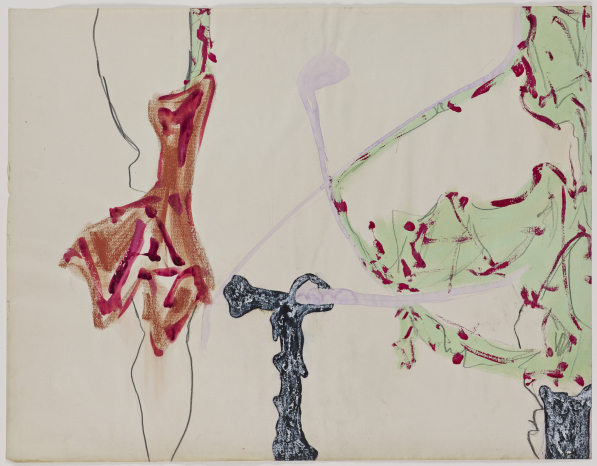

Once Beck began to unravel the energy of his inner world and its relations to physical reality, his production became nearly inexhaustible, and it is in this spirit, between 1950 and 1955 that he created nearly 50 percent of his entire body of visual work.

After 1955 until his last painting in 1958, Beck’s work became increasingly experimental, using all available means including painting, drawing, collage and the incorporation of objets trouvés. By the end of the 1950’s however, Beck halted work in this direction, creating his penultimate painting, The Sugar Industry, in 1958. In its manifestly political subject matter, The Sugar Industry looks out onto the vista of innovation that The Living Theater would continue to engage with in its dedication to political action and critique. It is as if Beck had reached the logical point of departure from painting on a flat surface, already indicated by his inclusion of three-dimensional objects erupting out of the works, to arrive at a new kind of painting of the body, painting in space, that is, a physical theater developed through a painter’s extended touch.

TEXT BY CAMERON SEGLIAS AND MARIE SCHLEEF